Reverse Weave is one of those terms that shows up everywhere in heritage menswear, yet the construction itself is rarely explained. It isn’t a trend and it isn’t a marketing term. It’s a small technical adjustment that made sweatshirts survive washing, keep their shape, and become the backbone of American athletic wear. The idea is straightforward, and once you understand it, both vintage and modern versions become far more interesting.

Early history

The story starts in 1919 with the Knickerbocker Knitting Company, founded by Simon Feinbloom in Rochester, New York. When Simon passed away a year later, his sons Abe and William took over and renamed the company Champion Knitting Mills. Their focus at the time was practical knitwear for workers and military schools.

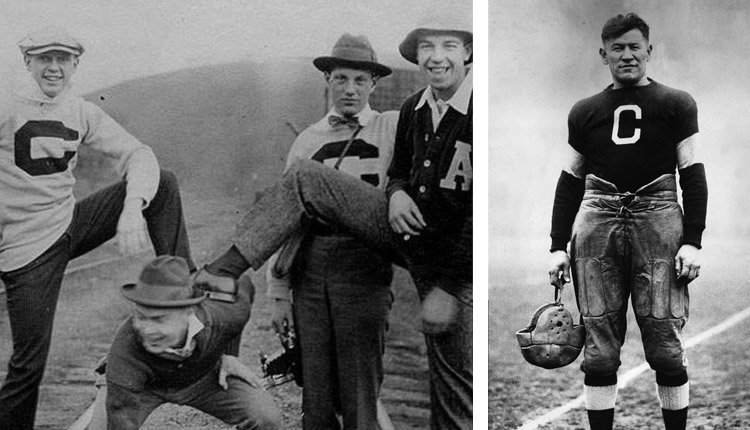

In the 1920s, Champion pieces were adopted by places like the Wentworth Military Academy. Wool sweatshirts worked well enough, but washing them was a nightmare. Cotton was cheaper, lighter, and easier to care for. Champion leaned into that and became one of the early producers of cotton athletic wear for universities across the country.

By the end of the decade, Champion sweatshirts were a common sight on campuses and training fields

The small complaint that changed everything

In 1928, Champion hired Sam Friedland, a cutter from Hickey Freeman. He brought technical garment knowledge the company didn’t have before. In 1934, a university equipment manager mentioned something that sounds almost too simple to matter: the sleeves didn’t shrink, but the bodies did.

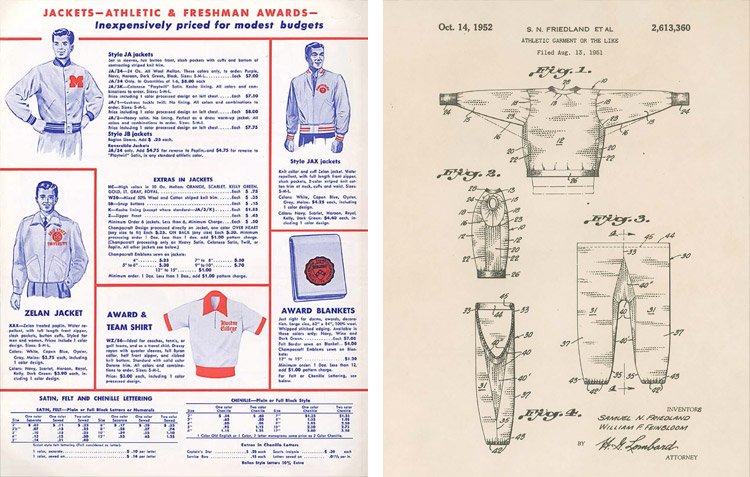

Friedland tried something basic. He cut the sweatshirt open, rotated the fleece so the grain ran horizontally, and added ribbed gussets at the sides so it still allowed movement. The result didn’t shrink in length after washing. That was the beginning of what Champion eventually patented as Reverse Weave.

Champion patented the idea in 1938 and refined it again in 1952. Inside the company it became known as the “family jewel.”

Why Reverse Weave mattered

Reverse Weave was a practical solution to an everyday problem. Turning the fleece sideways prevented vertical shrinkage. The gussets kept the fit comfortable. The ribbing at the cuffs and hem gave structure. It all came together in a silhouette that stayed square and clean after dozens of washes.

That durability is the reason so many 60-year-old examples still look better than modern sweatshirts after one season.

Modern interpretations

Only a handful of makers today produce something close to the original construction.

The Real McCoy’s

The Real McCoy’s version uses a 14oz fleece. It’s heavy, dense, structured, and feels closer to a military-issued sweatshirt than anything on modern shelves. The pattern, gussets, ribbing, and printing are all approached with an almost obsessive level of accuracy.

Warehouse & Co.

Warehouse takes a more vintage-inspired approach. Their fleece comes in around 12oz, very similar to classic Champion pieces from the 1960s and 1970s. It has a slightly softer hand, a more relaxed drape, and still uses the correct cross-grain body and ribbed side panels.

Champion

Champion still makes Reverse Weave today, but the quality varies by line and factory. Some pieces come close. Some don’t.

Vintage Champion is still a great option, although sizing is inconsistent and good condition pieces are getting harder to find.

What to look for when buying

A proper Reverse Weave has a few unmistakable details:

• the body cut horizontally

• firm, ribbed side gussets

• dense ribbing at cuffs and hem

• a heavier fleece weight

• clean, even stitching

• prints tied to universities or the military if you want something authentic

A simple fix that became a standard

Reverse Weave didn’t come from a design studio. It came from a small frustration and someone willing to try a different cut. Champion turned the experiment into a signature. Japan made it collectible. Today’s heritage brands push it further.

It survives because it does exactly what it was meant to do: hold up, wash well, and look better with time.